This article was originally published in PHP Architect Magazine in the April 2015 issue. I wrote a column called "Leveling Up" from January 2015 until June 2017. The content of the articles here are as they were originally published.

April 2015Leveling Up: TDD With PHPSpec

by David Stockton

In this edition of Leveling Up, we’re going to talk a bit about Test Driven Development, how it can help you write better software, and how the PHP software package, phpspec, can help you by encouraging a TDD workflow and good software design.

Introduction

Test Driven Development is not exactly new. It’s not even new for PHP. Kent Beck is credited with “rediscovering” TDD back in 2003. Old school programmers likely followed the TDD methodology back in the 1950s. Indeed, in 1957, D. D. McCracken wrote in “Digital Computer Programming” that customers should prepare acceptance test cases prior to, or at some time before, the program was complete. These acceptance test cases were a combination of known inputs and hand-calculated outputs that would be compared with the final output of the program. McCracken even encouraged the customers to be the ones to provide the test cases.

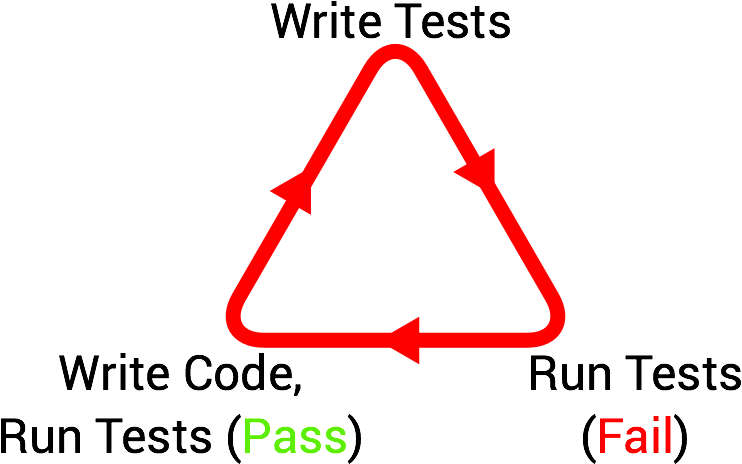

TDD is a software development methodology or process where the developer writes a test, runs the test so that it fails, writes the minimum amount of code to make it pass, and then repeats the cycle, adding more tests, adding and refactoring code and running the tests. This is commonly known as the red-green cycle with red indicating the failing tests and green representing passing tests.

The TDD development cycle

Hardly anyone would argue that testing our code isn’t important. In order to ensure that the code does what it should do (and equally important, doesn’t do what it shouldn’t do), we need to test it. This can be in the form of manual development testing that you do while writing the code, manual QA testing, user acceptance testing (UAT), integration testing, system tests, etc. In order to successfully grow a software system without needing to increase the number of people who test the code, it’s important to have tests that can be run over and over by the computer. By writing code that tests code, we have the ability to run this code on demand and in a fraction of the time it would take to run through manual testing.

Throughout this article, unless otherwise specified, I’ll be using the word testing to refer to unit testing specifically. This is testing on a unit, or small piece of code, usually a function or method, or even smaller. There are other types of testing, including other types of automated testing, but for now, we’ll focus just on unit testing. This also means that we should only be testing a single class at once. Our tests should not use the database, they should not use the file system, they should not use external APIs, and if our class is composed, or built with other classes, those other classes’ behaviors should be provided by mock objects. I’ll explain more about what mock objects are and how they work in part two.

TDD Pros and Cons

Test Driven Development has a lot going for it. If you follow the philosophy, every line of code should have a reason for being there. A failing test was the impetus for it being there. Because there are tests for every line of code, we have less of a chance for defects and regressions to occur. A regression is when previously working code is broken by a new change or an added feature. Since all the features have tests that are run all the time, we know that the behavior we’ve tested for continues to work. In general, TDD leads to better code quality. If the tests are hard to write, the code is likely hard to use. Simple tests lead to simpler code with less room for problems to grow.

Tests can be used to augment, or even in some cases, replace documentation. Again, if TDD methodologies are followed, the intent of the developer should be captured in the test. You will likely be able to determine if or why a particular behavior exists in code by seeing a test in place that caused that behavior to be written in the first place.

Codebases that have been written using TDD tend to lend themselves easier to refactoring; that is, changing the implementation but not the behavior of a class and its methods. Since the tests exist to ensure the behavior is consistent, refactoring can be extreme and the developer knows they haven’t inadvertently broken the desired behavior.

TDD doesn’t need to be a solo pursuit either. Several years back, I was practicing TDD with a coworker who was not familiar with it, and I was learning how it worked as well. I would write a series of tests against code that didn’t exist at all, and It allowed me to, and forced me to, think about how the various bits of code would fit and work together. I had a good idea about what I wanted to see created, but I described all of it through PHPUnit tests. Then I passed these tests over to my coworker, who implemented the actual classes using my tests as a guide. He’d often do the same in reverse, writing tests with which I would implement the classes he was describing. Working this way was very beneficial because it forced good design. Additionally, it led to increased communication and understanding of the codebase. If a test was internally inconsistent, we’d notice and go to the other developer, and showing the problem and asking about the intent. It also led to both of us knowing the codebase very well since we had either written the code or written the tests describing the code’s behavior. If you can work in a similar fashion, I’d highly recommend it.

Additional benefits of TDD include smaller codebases, (remember that each line of code is a liability, a potential way that defects and problems can sneak in), a reduced need for manual testing, and a fast feedback loop to help determine if an implementation is correct.

All of benefits are great, but TDD doesn’t come without a cost. Features written using TDD will usually take longer to develop, which means more money. TDD is a foreign concept to most people, so there is a learning curve. And it’s a learning curve that some developers don’t see the point in using. Sometimes tests are written that don’t provide much value. Time can be wasted on fixing or removing these, or on finding and removing “brittle” tests, that is, tests that rely too much on the actual implementation of functionality rather than on testing the behavior and outcome of a method. TDD also requires discipline on the part of the team implementing it. If members of the team are writing tests, but they write them after the code has been written, it is more likely they will miss edge cases, miss out on clarifying the intent of the code, and end up writing tests that make refactoring hard and changes more difficult and costly.

On new projects, starting from nothing with TDD means there’s a lot of overhead right from the start, setting up builds, unit test configurations, etc. It is often hard to quantify the exact cost savings versus up-front investment. In other words, it’s very difficult to prove that a defect that doesn’t exist because of following a TDD methodology or because the developer just didn’t make that particular mistake this time. For me, it’s been worth it when I did follow TDD. I can’t recall a time where I’ve wished I hadn’t spent time writing tests. However, in the times when I didn’t write tests, I’ve often wished I had, as I tracked down a tough bug or attempted a refactor without the safety net of a test suite. With all that being said, let’s now jump into phpspec.

phpspec history

Phpspec started in the fall of 2007. In 2011 was the first alpha release. Since then, it has slowly been gaining in popularity which seems to have accelerated just recently. It’s still nowhere near the popularity and usage of the ubiquitous PHPUnit, but I feel each of them has their own place in a developer’s toolbox. Phpspec takes some of the tedium out of getting started with testing your code, and because it is more limited in scope than a tool like PHPUnit, it will actually force better design on the resulting code.

Phpspec integrates code generation (which I’m generally not a fan of) in a way that’s unobtrusive and doesn’t seem to do anything objectionable. It can handle the tedious parts of creating a new file with a new class or new method stubs, which leaves you to write the actual code parts. If your coding style calls for certain comments or doc blocks, phpspec’s templates allow you to customize the output however you’d like. Back in the day, starting a new class with full docblocks in PEAR standard would mean about 50 lines of code and comments in each new file before getting to write even a single line of a method. Phpspec can take care of all of that if you want it to.

Installing phpspec

Installing phpspec is pretty simple with composer. Assuming you’ve already got composer (if not, go to getcomposer.org and follow the directions), you can get phpspec installed like so:

composer require phpspec/phpspec ~2.0

If you run this in a project where you already have a composer.json file, the above command will modify it to add the appropriate require directive. If you run this and you don’t have a composer.json, it will create one and install phpspec for you.

Phpspec will be installed in the vendor directory by default with the phpspec executable being found in vendor/bin/phpspec. To make it easier to run, you may want to consider adding vendor/bin to your PATH.

To ensure everything is working, try running phpspec with phpspec if you added it to your path, or vendor/bin/phpspec if not. You should see the phpspec help screen appear.

The TDD cycle with phpspec

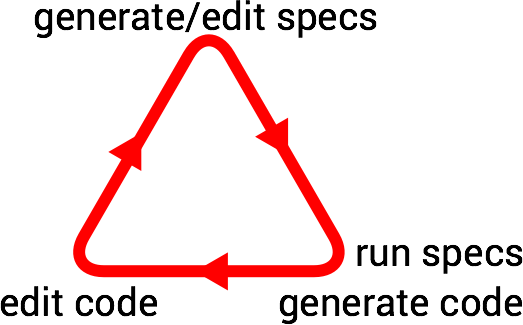

The red green cycle with phpspec is very similar to the TDD cycle. We start with generating or editing spec code. Then we run the spec. If phpspec detects that a class or method is needed and it doesn’t see that it already exists, it will ask if you’d like to generate it. This, while fairly simple, is one of the cooler features of phpspec and it takes away a lot of the tedium in the standard TDD cycle.

Once the classes and methods exist, you may need to edit the code to make the spec pass. You can then start the cycle over again by writing or generating more spec files. The cycle for TDD with phpspec should look fairly familiar. Instead of writing “tests”, we’re going to write “specs”. Phpspec will help us out a bit by generating the skeleton classes and specs. We still get to do all the fun parts though.

Building classes with phpspec

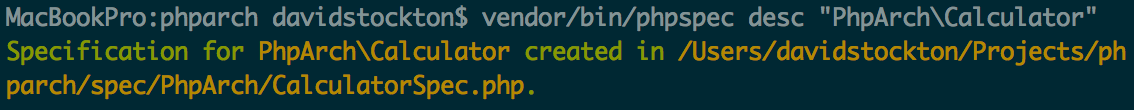

To help understand how phpspec works in practice, we’ll start a simple calculator class using TDD with spec. Start by telling phpspec to generate a spec for the calculator.

phpspec desc "PhpArch\Calculator"

Phpspec tells us that it has generated the spec. Let’s take a look:

Listing 1: Generated Spec for Calculator

<?php

namespace spec\PhpArch;

use PhpSpec\ObjectBehavior;

use Prophecy\Argument;

class CalculatorSpec extends ObjectBehavior

{

public function it_is_initializable()

{

$this->shouldHaveType('PhpArch\Calculator');

}

}

Now there’s really not a whole lot there. We’ve got an automatically generated spec which essentially says, “The PhpArch\Calculator class should exist.”. Now we’ll run the spec.

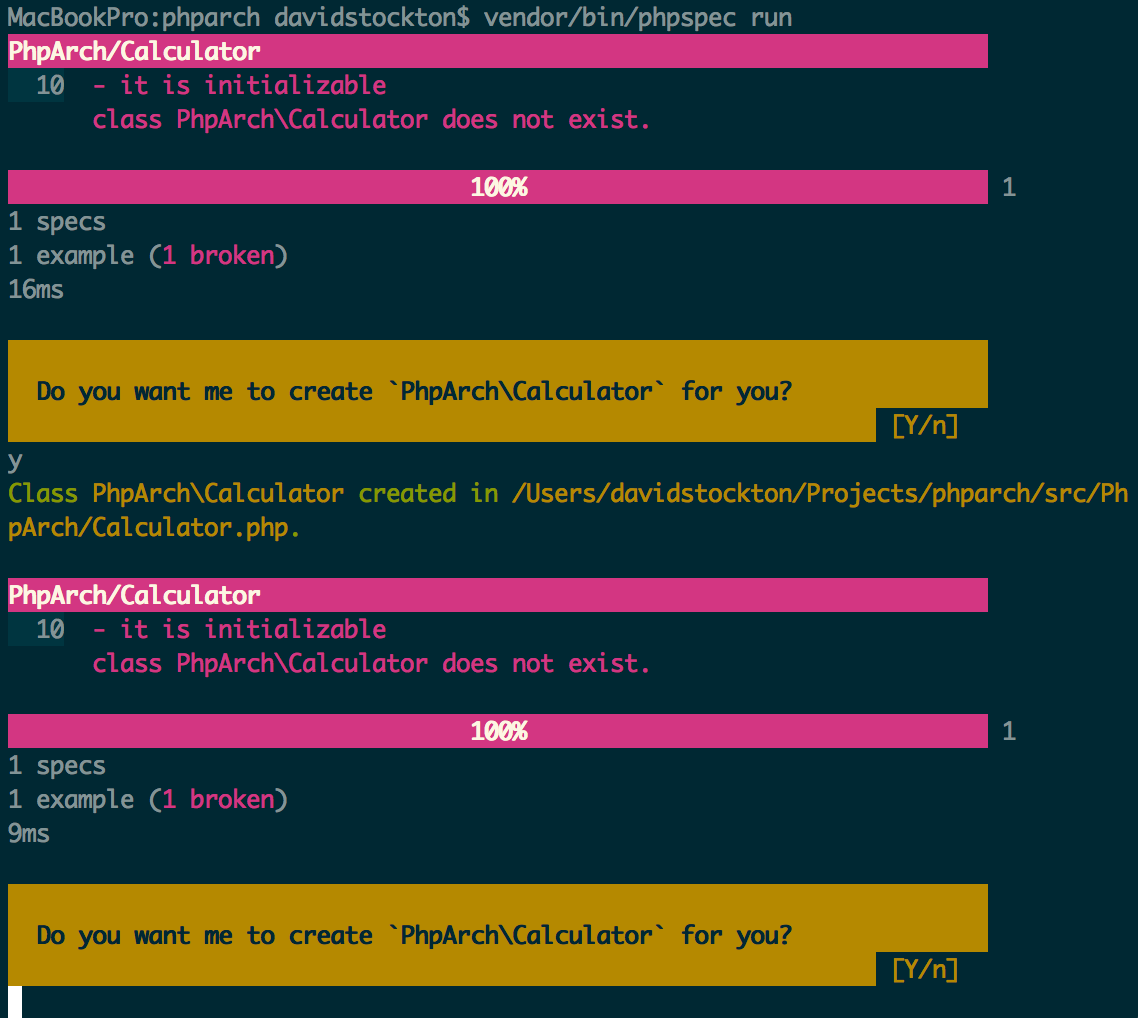

phpspec run

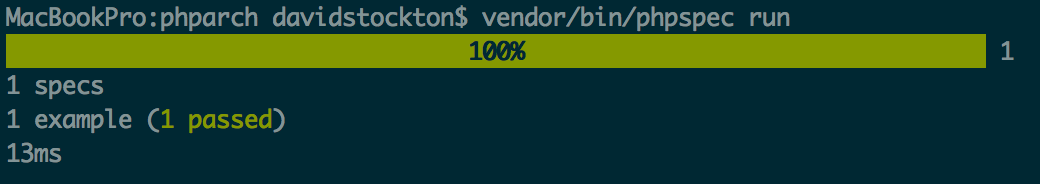

And as output, we’ll see figure 2.

So let’s review what happened. First, we immediately see a failure. Our PhpArch\Calculator spec indicates that the class should exist, but the test fails because at this point, it doesn’t exist. Phpspec helpfully asks to generate our class, so of course, yes, please do this for us.

If you respond ‘y’ for yes, phpspec indicates that it created our class in the usual place. If we look in that path, you’ll see it’s telling the truth. It will then run the specs for us again automatically. You can see now that the class exists, everything is… hmm, broken. And it again asks us if we’d like it to generate the class that it already generated. If you say yes again here, it will ask if you want to overwrite the file that already exists. So I’ve stopped it.

What’s going on? It turns out the answer lies with the autoloader. Phpspec uses the autoloader to load all the classes it will be testing and currently, our autoloader is provided by composer and it doesn’t have a clue about how to load our new calculator class. Let’s fix that.

We need to add the following bit to our composer.json file:

"autoload": {

'psr-4": {

"": "src"

}

}

Once this is in place, we can tell composer to make a new autoloader for us:

composer dumpautoload

Now, let’s run phpspec again (see figure 3):

It now works. Hooray!

Now refer back to listing 1, and let’s go over the spec code. First of all, it’s just plain PHP. We’ve got a namespace and some use bits, but the interesting part is the method, it_is_initializable. If you’re like me and follow a coding standard, specifically one that says methods should be camelCased and have visibility modifiers, this probably looks bad. It’s not something you can change though, and after working with it for a bit, you may decide you don’t want to either. The phpspec team chose to go with underscore separated words and it does make your spec look different from your code.

The next important bit is the $this keyword. Normally, we think of $this as being an instance of the object of the class we’re using. In phpspec, this is also true, as it’s just PHP. However, $this should really be thought of as our SUT, or System Under Test. That means $this->shouldHaveType('PhpArch\Calculator'); indicates to phpspec that the code we’re testing should be a PhpArch\Calculator. Indeed, our test is a wrapped version of our Calculator, which means we can set up behaviors and expectations as well as test return values. Instead of using methods like $this->assertEquals() like you may be used to in phpunit, phpspec uses matchers. Let’s try it out by writing some more spec. Add this method to your CalculatorSpec.php class:

function it_can_add_two_integers()

{

$this->add(2, 2)->shouldBe(4);

}

First of all, the name of the method is important. Phpspec specifications start with the word ‘it’ or ‘its’ andeparating words by underscores allows phpspec to print out the purpose of the test in an easy to read way.

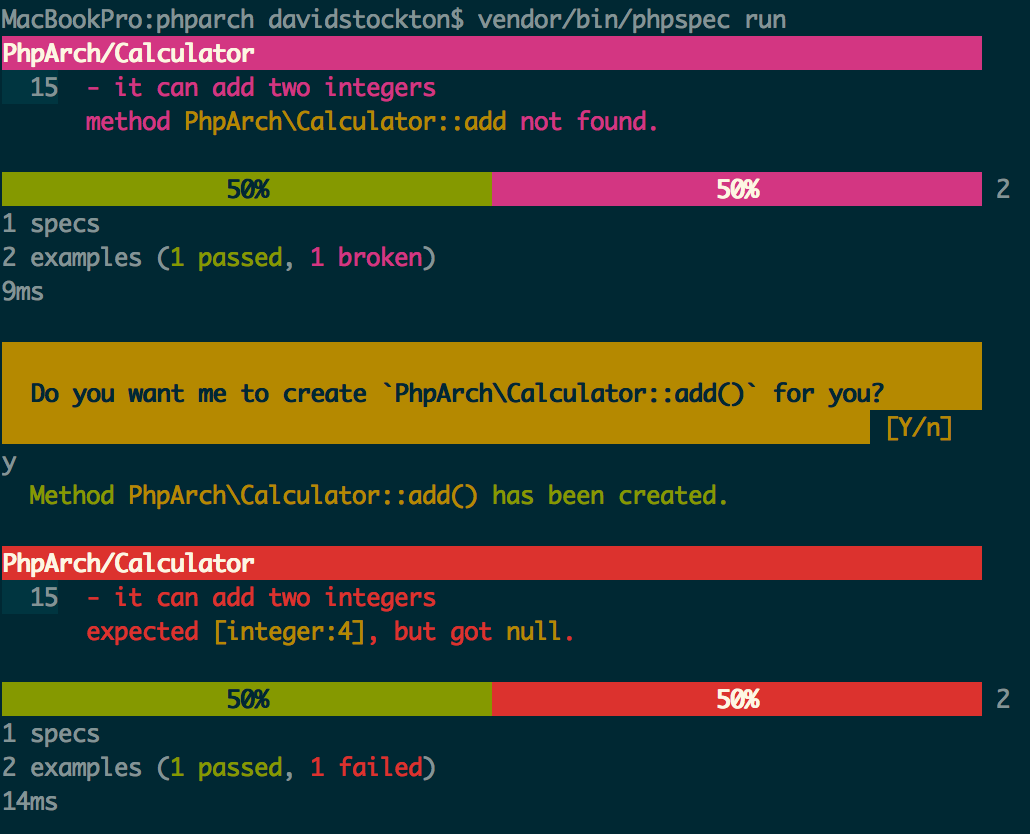

Next in our spec, remember that $this refers to our calculator. We’re telling phpspec that when we call the add method with 2 and 2, it should return 4. The shouldBe method is a built-in matcher that does the equivalent of an === check against the return value of the add method. Let’s run our spec again with vendor/bin/phpspec run and see what happens (figure 4).

Now when we run our spec, phpspec is able to determine that the Calculator class doesn’t have an add method. It indicates we have one broken test: the “it can add two integers” test (defined on line 15). It then asks us if we’d like it to create that method for us. Yes please!

Once it creates the method, it runs the spec again and our test changes from broken to failed. This is because the method it added was empty and does nothing, so intead of getting 4 as it expected, it got null. We now have 1 passing test (the class exists) and one failing test (our calculator cannot add).

Now it’s time to move to the writing code/refactoring code part of TDD. Let’s update our add method to the following:

public function add($argument1, $argument2)

{

return 4;

}

If we run phpspec again, you’ll see that all the tests pass. Clearly, this is a problem, right? Not really. In TDD, we try to not make assumptions and write more code than needed to. In fact, we now have a calculator that works really well for adding any two numbers whose sum is 4. The problem isn’t that our method returns 4, it’s that we don’t have enough tests to ensure that our code does anything other than returning 4.

Let’s add another line to our spec:

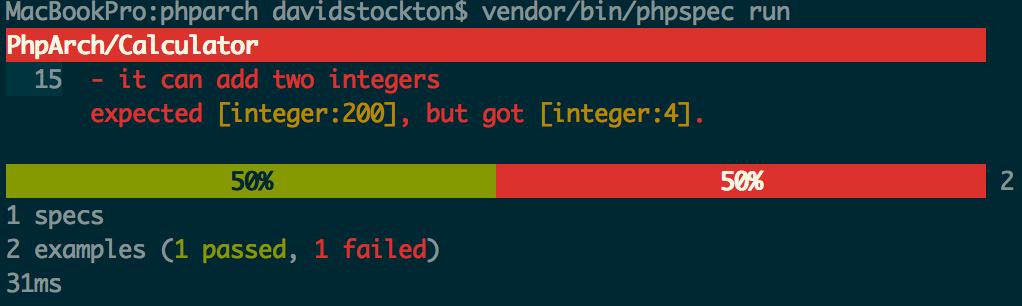

$this->add(100, 100)->shouldBe(200);

Now, when we run phpspec again, we see a failure:

Our spec now indicates that we should be able to add up numbers that total to something other than 4. And again, we move back into our refactoring and editing code phase. Now, let’s update our add method to the following:

public function add($x, $y)

{

return $x + $y;

}

Running phpspec again will show that all of our tests are passing again.

We would continue this way, adding spec code to indicate how the behavior of our calculator should be and then watching it fail, then adding or editing code to make the spec pass. I would encourage you to do just that, and to add spec to make your calculator subtract, multiply and divide.

I would also argue that we may not be done with our add method. To make this class more robust, we may want to specify what happens if the user sends in unexpected types. We can deal with them in whatever way we see fit. (As I’m writing this, the php internals vote for strict type hinting has just passed 108-48 today, so sometime in the not-so-distant future, we may be able to control what scalar types are allowed into a function or method, but for right now, we have to deal with it.)

Phpspec allows us to specify the behavior and the intent of our code. Knowing the intent, or why the code was written or designed in a particular way, helps future you, or future maintainers of the code know why the code was written in a certain way. We could specify that our class should throw an exception if non-numerics are passed in, or non-integers, or negative numbers, or whatever else we wanted. By laying out all of this in our spec, we’re removing a lot of the ambiguity and guessing games that may come when a future developer decides that it’d be really nice to, for instance, concatenate strings using the add method (why?). If we have tests showing our method should throw an exception, there’s probably a good reason for it – perhaps some other code is relying on that exception being thrown?

Conclusion

This was a quick and dirty introduction to TDD and phpspec. You’ve learned how to get started with the TDD workflow, as well as what to be aware of as far as the tradeoffs with TDD. We’ve talked about how to build basic classes using phpspec to generate skeleton spec and classes, and then how to add new spec to describe new desired behavior and functionality of our classes. Next month, in part two, we’ll dive a bit deeper and learn how we can leverage phpspec to build more complex classes that interact with and are composed of other classes. This will bring in the topic of mocks and how we can use them to write good tests to ensure our code is doing what it should.

tags: php - TDD - phpspec - unit testingBiography

David Stockton is a husband, father and Software Developer. He is VP of Technology at i3logix in Colorado leading a few teams of software developers building a very diverse array of web applications. He has two daughters, 11 and 9, who are learning to code JavaScript, Python, Scratch and PHP as well as building electrical circuits and a 3 year old son who has been seen studying calculus and recursive algorithms. David is an active proponent of TDD, APIs and elegant PHP.